Your Body’s Antibiotic Factory: The Proteasome

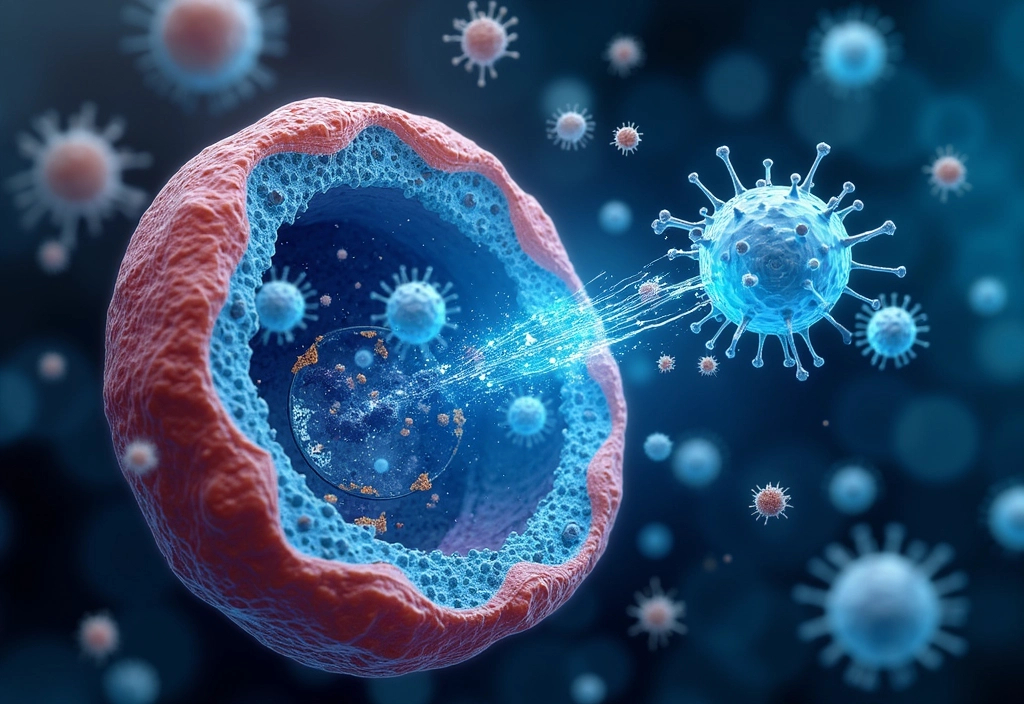

For years, scientists believed the proteasome—a cellular machine that shreds proteins—served only one key immune function: helping T cells recognize infected cells by generating antigen fragments. That view just changed.

A groundbreaking study reveals that proteasomes also create tiny, infection-fighting molecules known as proteasome-derived defense peptides (PDDPs). These naturally occurring peptides work like antibiotics by disrupting bacterial membranes—and your body makes them constantly.

What Are PDDPs?

PDDPs are short, positively charged (cationic) peptides with antimicrobial properties. Unlike traditional antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) that are encoded and expressed as standalone proteins, PDDPs emerge as byproducts of normal protein degradation. While breaking down unwanted proteins, the proteasome also generates protective fragments—essentially recycling trash into weapons.

This process gives cells an instant defense tool, even before the immune system deploys antibodies or immune cells.

Infection Triggers a Powerful Upgrade

When bacteria invade, cells don’t just passively respond—they reprogram their proteasomes. A regulatory subunit called PSME3 gets recruited to the proteasome, changing its cleavage behavior. As a result, the proteasome produces peptides that are even more effective at piercing bacterial membranes.

This mechanism acts as an early-warning strike system, enabling cells to kill invaders on the spot.

Lab Tests Show PDDPs Kill Drug-Resistant Bacteria

To test the theory, researchers used mass spectrometry to identify peptides formed during proteasome activity. They predicted over 270,000 potential antimicrobial peptides across the human proteome. Several top candidates were synthesized in the lab and tested on both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

One peptide, derived from the protein PPP1CB, stood out. It killed harmful bacteria with a potency comparable to the antibiotic tobramycin—and even worked in mouse models of pneumonia and sepsis. Unlike many traditional antibiotics, these peptides didn’t harm human cells.

A New Strategy Against Antibiotic Resistance

Antibiotic resistance remains a global health crisis. Traditional drug pipelines struggle to keep pace with evolving pathogens. PDDPs could offer a powerful alternative. Since our bodies already produce them, these peptides might be better tolerated and less likely to trigger resistance.

Researchers believe PDDPs could be engineered into next-gen antimicrobial drugs, especially for treating antibiotic-resistant infections.

Open Questions and Future Potential

This discovery raises exciting questions for immunology and biotech:

- How do different tissues regulate PDDP production?

- Can we enhance PDDP activity using drugs or gene editing?

- Do these peptides work together for greater effect, like immune cell swarms?

- Could similar systems protect against viruses or fungi?

The authors propose a new concept: proteolysis-driven immunity. This term reflects how cells defend themselves by breaking down proteins to produce antimicrobial agents—a dual-purpose system that supports both adaptive and innate immunity.

Check out the cool NewsWade Youtube video about this article!

Article derived from: Jangra M, Travin DY, Aleksandrova EV, Kaur M, Darwish L, Koteva K, Klepacki D, Wang W, Tiffany M, Sokaribo A, Coombes BK, Vázquez-Laslop N, Polikanov YS, Mankin AS, Wright GD. A broad-spectrum lasso peptide antibiotic targeting the bacterial ribosome. Nature. 2025 Mar 26. doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-08723-7. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40140562.